In 1957, Otto Habsburg-Lothringen, son of the last Austrian Emperor Charles, was issued a certificate confirming his Austrian citizenship. However, under the Habsburg Law (State Law Gazette No 20/1919) he was still banned from entering Austria. A note in his passport said that the document did not entitle him to enter into or transit through Austria. The political and legal controversies over the Habsburg matter were even brought before the Constitutional Court and the Administrative Court. At the height of the crisis, the Socialist Party of Austria spoke of a “lawyers’ coup d’état”. It was not until 1966 that Otto Habsburg set foot Austrian territory for the first time.

The roots of the conflict dated back to the early years of the Republic. After the First World War, the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the establishment of the Republic of German-Austria, the Habsburg Law was passed in 1919 in the interest of “the security of the Republic”. Under this law, former Emperor Charles was unconditionally “banished from the country”, whereas the right of the other members of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen, the ruling dynasty of the Monarchy, ever to return to Austria was subject to certain conditions. Pursuant to section 2 of the Habsburg Law, they had to sign a declaration of loyalty to the Republic and explicitly renounce their membership of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen and all sovereign rights emanating therefrom. It was up to the State Government, upon consultation with the Main Committee of the National Assembly (now: the Federal Government in consultation with the Main Committee of the National Council), to decide whether this declaration was to be regarded as sufficient. The crucial moment came at the beginning of the 1960s. On 5 June 1961, Otto Habsburg-Lothringen submitted the following declaration to the Federal Government, requesting a statement by the latter that the declaration was deemed sufficient pursuant to section 2 of the Habsburg Act:

“I, the undersigned, herewith declare, pursuant to Section 2 of the Act of 3 April 1919, State Law Gazette of the State of German-Austria No. 209, that I explicitly renounce my membership of the House of Habsburg-Lothringen and all sovereign rights emanating therefrom, and profess myself to be a loyal citizen of the Republic. In witness whereof I have signed this declaration by my own hand. Pöcking, 31 May 1961. Otto Habsburg-Lothringen“.

The Federal Government was unable to agree on a joint position. In a paragraph subsequently added to the minutes of the Ministerial Council meeting of 21 June 1961, it was stated that the application was herewith deemed denied. Finally, an official note was published in the “Wiener Zeitung” of 14 June 1961: “In the absence of an agreed position and given the constitutional law in effect, the declaration is deemed to be rejected.” The declaration was never transmitted to the Main Committee of the National Council. Nor was Otto Habsburg-Lothringen, as the person concerned, ever informed of the result of his application, either orally or in writing.

Otto Habsburg-Lothringen filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court against the “resolution” of the Federal Government pursuant to Article 144 of the Federal Constitutional Law. The Constitutional Court rejected the complaint by a decision pronounced on 16 December 1961 (VfSlg 4126), stating that the body called upon to decide on this matter, i.e. the “Federal Government in consultation with the Main Committee of the National Council”, was not an administrative authority in the meaning of Article 144 of the Federal Constitutional Law, and that, consequently, this was not a case brought against an administrative notice (but rather – though never stated explicitly – a kind of sovereign act outside the scope of the courts). Arguing that the Federal Government had to act in agreement with the Main Committee of the National Council, which was not an administrative body, as its members exercised a constitutionally guaranteed free mandate and therefore were not bound by the legal opinion of the Constitutional Court, the Court declared the matter to be outside the scope of its jurisdiction.

Otto Habsburg-Lothringen’s next step was to lodge a complaint for undue delay of proceedings with the Administrative Court, which, having convened an enlarged senate, finally (in lieu of the Federal Government) pronounced its decision on 24 May 1963 (VwSlg 6035 A/1953), stating that the declaration submitted by Habsburg-Lothingen was to be taken as sufficient, whereby the complainant’s ban to enter the country was deemed to be lifted. The Administrative Court considered the participation of the Main Committee of the National Council to be derogated.

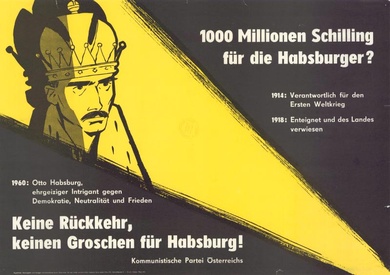

This decision triggered a storm of protest on the part of the Socialist Party (“a lawyers’ coup d’état”) and the Freedom Party. Strikes, protest demonstrations and furious exchanges in Parliament followed. An authentic interpretation of section 2 of the Habsburg Law as a constitutional act re-established the necessary agreement between the Main Committee of the National Council and the Federal Government (Federal Law Gazette 172/1963). Otto Habsburg-Lothringen entered Austria for the first time in 1966. However, the Habsburg crisis was not fully resolved until 1972, when Federal Chancellor Bruno Kreisky (SPÖ) shook hands with Otto Habsburg-Lothringen on the occasion of a meeting of the Pan-European Movement in Vienna.

Subsequently, the Constitutional Court’s reasoning, as outlined in VfSlg 4126/1961, was subject to frequent criticism: One of the arguments raised against it was that the refusal of entry into Austria could have been justified by the fact that a resolution by the Federal Government had never been adopted, given that according to prevailing opinion Ministerial Council decisions must be unanimous in order to be effective.