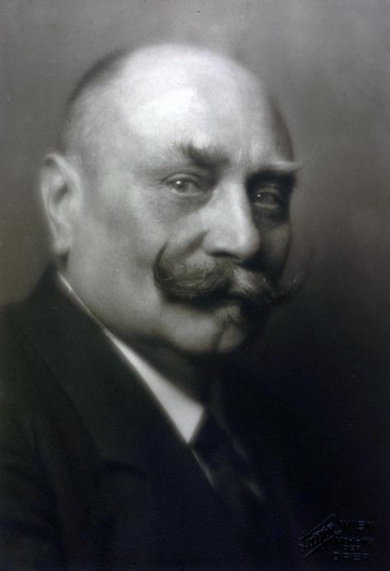

“Sever marriages”, a term to be found in legal literature, are named after Albert Sever, the Social-Democratic governor of Lower Austria (then still including Vienna) from 1919 to 1920, who frequently made use of the possibility of granting Catholics wanting to remarry a dispensation for impediments to marriage by way of an administrative act. After 1918, this practice was equivalent to breaking a taboo: Marriage law was regulated under the General Code of Civil Law and, continuing the tradition of the Monarchy, denominationally oriented. For Catholics, therefore, the only way to terminate a matrimonial partnership was “separation from bed and board” with continuance of the marriage bond. The possibility of a formal divorce and remarriage was denied to them. The Social Democrats and the advocates of a Greater Germany both called for the introduction of obligatory civil marriage (to be performed before a public authority instead of the church) and the possibility of divorce, but they failed in their demands on account of strict opposition from the Christian-Social Party.

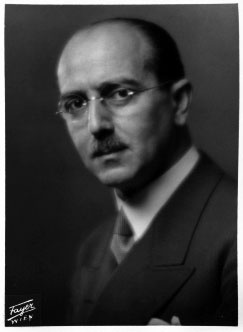

Against this background, people wishing to divorce could only resort to section 83 of the General Code of Civil Law, which allowed the “provincial body” to grant a dispensation for impediments to marriage for important reasons. Whereas before 1918 such dispensations had been granted very rarely as an act of grace by the monarch, this became almost common practice after 1918 in Lower Austria under Governor Sever, and after the separation of Vienna from Lower Austria also in social-democratic Vienna (1921-1934) and in some parts of Carinthia. There were days on which Governor Sever signed up to 100 dispensations, as he himself admitted in his autobiography.

Legal opinions on the admissibility and effects of dispensations as well as their consequences differed: Was an existing marriage bond an impediment subject to dispensation at all? Could a marriage bond be dissolved by an administrative act and protect those who remarried from criminal prosecution for bigamy? Or was there no such effect? Was marriage by dispensation therefore even valid? Or were there two marriages, both valid at the same time? The civil-law consequences (inheritance and family law, provision for widows, pension law) were equally unclear.

As described in contemporary literature, this controversy resulted in a complete “muddle”: Administrative authorities issued countless dispensations, which the Administrative Court and the Supreme Court repealed or refused to recognise. In the Supreme Court’s opinion, courts had the right to review dispensations as a prior issue in marital nullity proceedings and had to declare marriages by dispensation invalid by a judge’s verdict, which they frequently did. Thus, marriages by dispensation were permanently at risk of being declared invalid by a court.

Finally, the Constitutional Court intervened: In its landmark decision of 5 November 1927 (VfSlg 878), it repealed a judgement pronounced by a civil court, which had declared a marriage by dispensation invalid. The Constitutional Court ruled that the case constituted an (indirect) positive conflict of jurisdiction between an administrative authority and the judiciary. It stated that the administrative authority had the sole power to grant a dispensation, while courts did not have the power to decide independently on this preliminary issue. Thus, the Constitutional Court sharply contradicted the jurisprudence of the other supreme courts. In view of the ideological sensitivity of the matter, this instantly resulted in heated academic controversies, massive political criticism of the Constitutional Court, and violent media attacks against the special reporter of the case, i.e. Professor Hans Kelsen.

According to Kelsen, the issue of marriage dispensations was a scandal and a problem of legitimacy of the state. “The state, which explicitly allowed a (new) marriage to be concluded by its administrative authorities, declared this same marriage invalid by way of its courts. A more detrimental way of undermining the authority of the state is hardly conceivable.” As Kelsen himself noted, he had no doubt whatsoever that a conflict of jurisdiction existed. He referred to this possibility when a lawyer sought his advice, and, as special reporter of the Constitutional Court, he prevailed with his opinion.

The Constitutional Court maintained this line of jurisprudence in about 170 cases until the end of 1929. The reaction by the Supreme Court was to regard dispensations as administrative acts that were absolutely null and void, because they made double marriages possible. Hence, courts were free to continue to declare marriages by dispensation null and void, except in cases in which the Constitutional Court had already pronounced on a conflict of jurisdiction. These were the only decisions that were binding for the courts; they were barred from reviewing these dispensations and had to recognise them as legally valid.

Finally, the conflict over marriages by dispensation was one of the reasons for the alleged “depoliticisation” of the Constitutional Court through the 1929 amendment to the Federal Constitutional Law. In reality, however, the Court was “repoliticised”: All the members of the Constitutional Court were recalled under the amended law and were then replaced by way of new appointment modalities and the introduction of an age limit of 70 years.

Hans Kelsen, the main author of the Austrian Constitution, could have returned to the Constitutional Court upon a proposal made by the Social-Democratic Party, but vehemently refused to do so. He accepted a chair at the University of Cologne and left Austria, profoundly embittered by personal attacks and the circumstances of the Court’s depoliticisation.

By its decision of 7 July 1930 (VfSlg 1341), the newly appointed Constitutional Court departed from the line of reasoning followed by Kelsen since 1927 and returned to its earlier jurisprudence. From then on, the Court maintained that it did not have the power to pronounce on cases of marriage by dispensation, as there was no conflict of jurisdiction. The notion of an indirect positive conflict of jurisdiction was a thing of the past.

Modern doctrine (especially representatives of the pure theory of law) and jurisprudence unanimously hold that Kelsen’s solution was not convincing in dogmatic terms and that the problems at issue represented a conflict of mutual recognition rather than a conflict of jurisdiction. The latter would only exist if two public authorities were to claim jurisdiction in the main issue, whereas in a conflict of mutual recognition it has to be clarified whether a public authority deciding on the main issue is bound by the final decision taken by another authority in a preliminary issue.

However, for the individuals concerned – about 70,000 couples reportedly lived in “Sever marriages” in 1935 – there was no legal certainty before 1938, when German marriage law entered into force on the territory of former Austria and obligatory civil marriage was introduced. About 49,000 Austrian separations from bed and board were converted into fully effective divorces. After the end of the Nazi dictatorship in 1945, the marriage law, with its provisions on civil marriage and divorce, was cleared of its traces of National Socialism and adopted by the Republic of Austria.