-

-

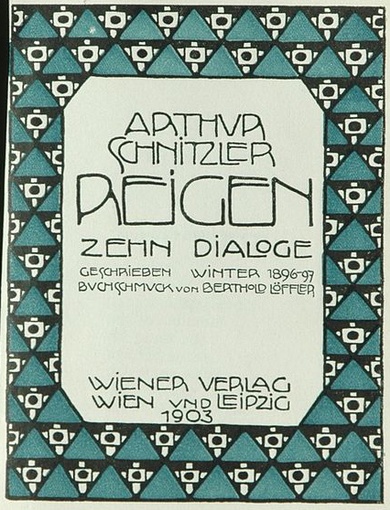

1921: La Ronde

-

-

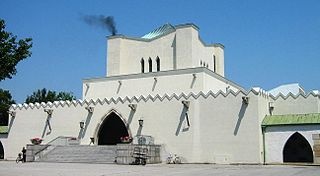

Vienna Central Cemetery, Crematorium.

(Foto: Invisigoth67 CC BY-SA 2.5)The Crematorium was built according to a design by Clemens Holzmeister and opened by Jakob Reumann on 17 December 1922.

Jakob Reumann, Governor of the Province of Vienna (1920–1925).

(Photo: Die Unzufriedene. Eine unabhängige Wochenschrift

für alle Frauen, 8. August 1925, S. 1 - ÖNB ANNO)The Social-Democratic governor had already appeared before the Constitutional Court in a case of dispute between authorities of the state (see 1921: Reigen).

-

1923: The Vienna Crematorium

-

-

1927: Dispensation instead of divorce

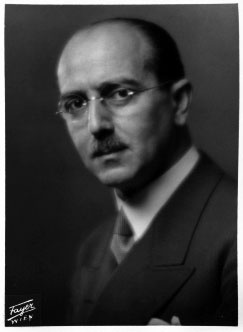

Prof. Dr. Hans Kelsen, ca. 1925.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

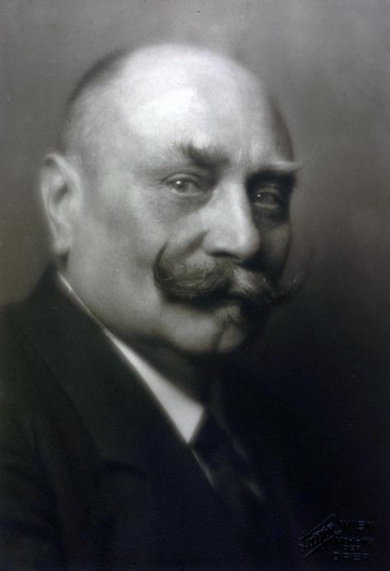

Albert Sever, Governor of Lower Austria, 1919–1920,

granted dispensations liberally.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

“Professor Dr. Hans Kelsen was not appointed to the new Constitutional Court, although he himself had created this supreme body of the judiciary.”

Cartoon in „Der Morgen. Wiener Montagblatt, 10.02.1930“, S. 7.(Photo: ÖNB/ANNO)

“Member of Parliament Albert Sever, the father of marriages by dispensation”

Cartoon in „Der Morgen. Wiener Montagblatt, 04.08.1930“, S. 7. (Photo: ÖNB/ANNO)

The Freethinkers’ Union calls for protest demonstrations against the departure from the Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence on marriages by dispensation and demands a reform of marriage law, 1930.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

-

-

News item in the Neue Wiener Abendblatt

reporting the repeal of the regulation

Neues Wiener Abendblatt, 23/06/1931, p. 1.

(Photo: ÖNB/ANNO)

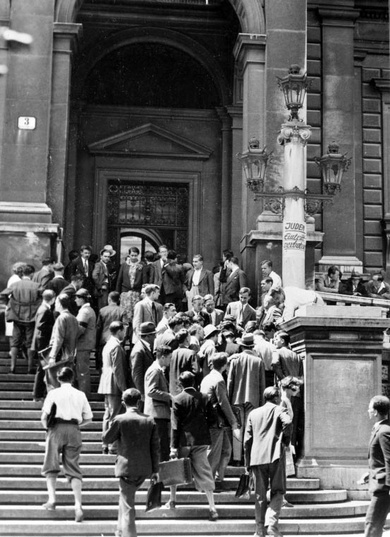

Student groups in front of the main entrance to the University of Vienna on 23/06/1931.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

News item in the Arbeiterzeitung reporting the Court’s decision

Arbeiter-Zeitung, 24/06/1931, p. 1.

(Photo: ÖNB/ANNO)

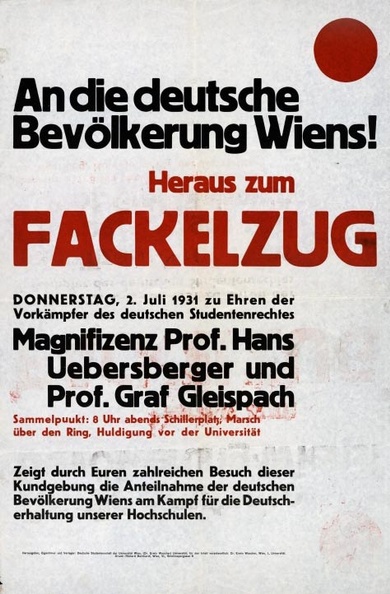

Call for a torchlight march in honour of the “pioneers of German student rights”, Rector Professor Uebersberger and former Rector Professor Gleispach, on 02/07/1931.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

Rector Uebersberger and Vice-Rector Gleispach during the torchlight march on 2 July 1931, surrounded by students raising their arms in the “German salute”.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)-

1931: The Vienna Student Regulation

-

-

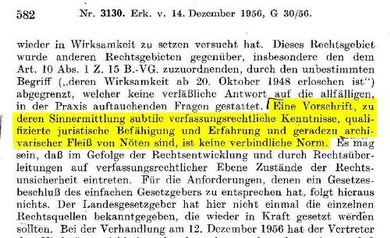

1956: An “Archivist’s Diligence”

-

-

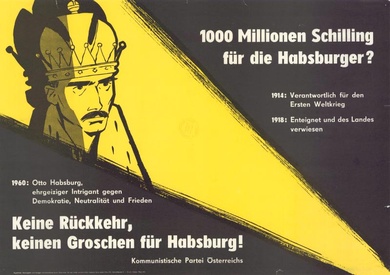

Poster of the Communist Party of Austria against Otto Habsburg-Lothringen’s return to Austria, 1960.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

On 14 June 1961, an official communication was published in the Wiener Zeitung, stating that the Council of Ministers had been unable to agree on the matter of Otto Habsburg-Lothringen.

(Photo: VfGH/Pauser)

Demonstration against Otto Habsburg-Lothringen’s entry into Austria on 23 December 1968.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)

The legendary handshake between Bruno Kreisky and Otto Habsburg-Lothringen on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Pan European Movement, 1972.

(Photo: ÖNB/Bildarchiv)-

1961: The Habsburg Crisis

-

-

1974: The First-Trimester Rule

Demonstration against the first-trimester rule in front of the Parliament building in 1979.

(Photo: ÖNB Bildarchiv)

Demonstration in favour of the first-trimester rule in 1984.

(Photo: ÖNB Bildarchiv)

-

-

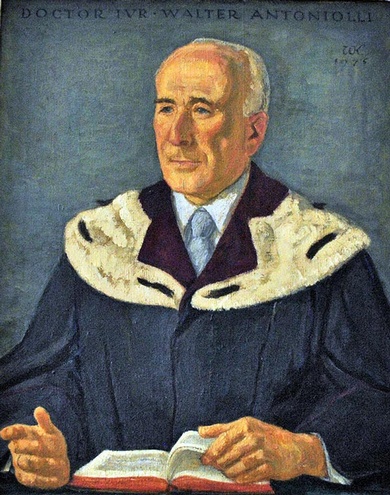

Walter Antoniolli, President of the Constitutional Court.

(Photo: VfGH/Pauser)

The 1975 University Organization Act.

(Photo: VfGH/Pauser)

Federal Minister of Science and Research Hertha Firnberg.

(Photo: ÖNB Bildarchiv)-

1977: The University Organization Act and the Resignation of the Constitutional Court President

-

-

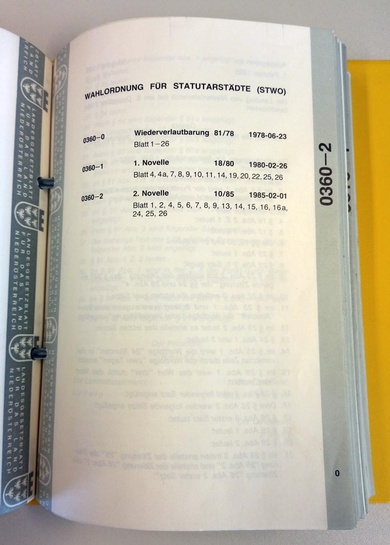

1985: Postal Voting Declared Unconstitutional

-

-

Wilfried Haslauer sen.

(Photo/excerpt: Wolfgang H. Wögerer, Vienna, Austria, CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Announcement of the decision of the Constitutional Court.

An ORF news broadcast on the public announcement of the decision on this case from 1985 can be found in the ORF-TVthek: Die Geschichte Salzburgs

Causa Ladenöffnungszeiten vor VfGH .

(Friday, 28/06/1985, 08:00 am, 04:45 min)-

1985: Wilfried Haslauer sen.

-

-

1986: Taxi Licenses

Roof-top taxi sign.

(Photo: Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 4.0)

-

-

Interior of a videotheque.

(Photo: Arne Müseler / CC-BY-SA-3.0)

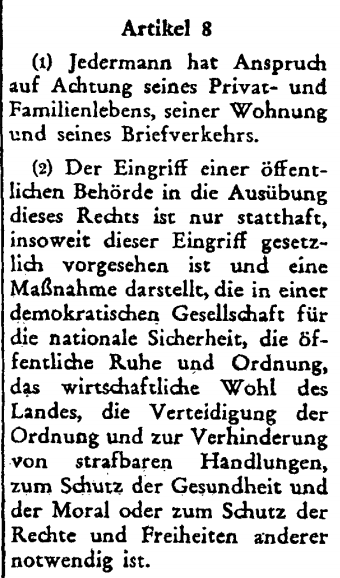

Art. 8 ECHR – Right to respect for private and family life.

(Source: Federal Law Gazette No 210/1958)-

1991: An Unconspicuous Private Life

-

-

2001: Unconstitutional Constitutional Law

-

-

Bilingual place name sign of St Jakob im Rosental / Šentjakob v Rožu.

(Photo: Gugganij, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Carinthian Governor Jörg Haider at the public promulgation of the repeal of the (monolingual) place name signs “Eberdorf” and “Bleiburg” as used in a “place name signs regulation” of the administrative authority of the district of Völkermarkt by the Constitutional Court on 26 June 2006 (VfSlg 17.895).

(Foto: APA)

Carinthian Governor Jörg Haider “circumventing” the Constitutional Court decision by mounting small additional signs in Slovene instead of bilingual place name signs in Bleiburg on 25 August 2006.

(Photo: LPD Kärnten)

Resolution of the conflict in 2011.

(Diagramm: APA)

Ceremony marking the resolution of the conflict over place name signs in the Wappensaal of the Provincial Parliament in Klagenfurt on 16 August 2011.

(Photo: LPD Kärnten)

Putting up the bilingual place name sign of Hart/Ločilo (Community of Arnoldstein) on 28 August 2011.

(Photo: LPD Kärnten)-

2001: Place Name Signs in Carinthia

-

-

2012: The European Fundamental Rights Charter

Preamble to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

(Photo: Trounce, CC BY 3.0)

-

-

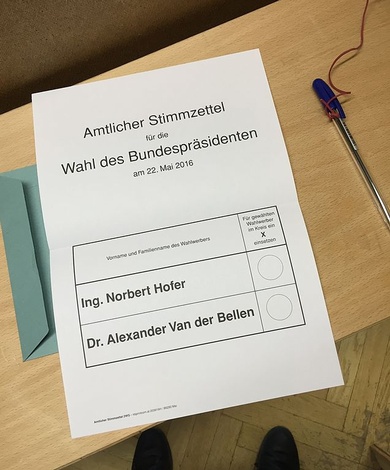

Ballot paper for the second (repealed) round of the election (run-off election of the federal president) in the polling booth.

(Photo: Christian Michelides, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The members of the Constitutional Court during the public hearing on the electoral process for the run-off election of the federal president.

(Photo: Christian Michelides , CC BY-SA 4.0)

The public announcement of the decision was broadcast live on Austrian television (ORF) on 1 July 2016.

A recording of the public announcement is available in the ORF TVthek: “Bundespräsidentenwahlen in Österreich” (Elections of the Federal President in Austria – only available in German)

To watch the video, click on the following link:

Historisches Urteil: VfGH erklärt Stichwahl für ungültig

(Landmark Decision: Constitutional Court Declares Runoff Election Null and Void” – only available in German)

(Friday, 1 July 2016, 11:55, 34:16 min.)-

2016: Run-off Election of the Federal President

Historic Case Law

Selected historic decisions and their social and political environment

Selected historic decisions and their social and political environment